Sea of Ink - Richard Weihe

'water rendered visible'

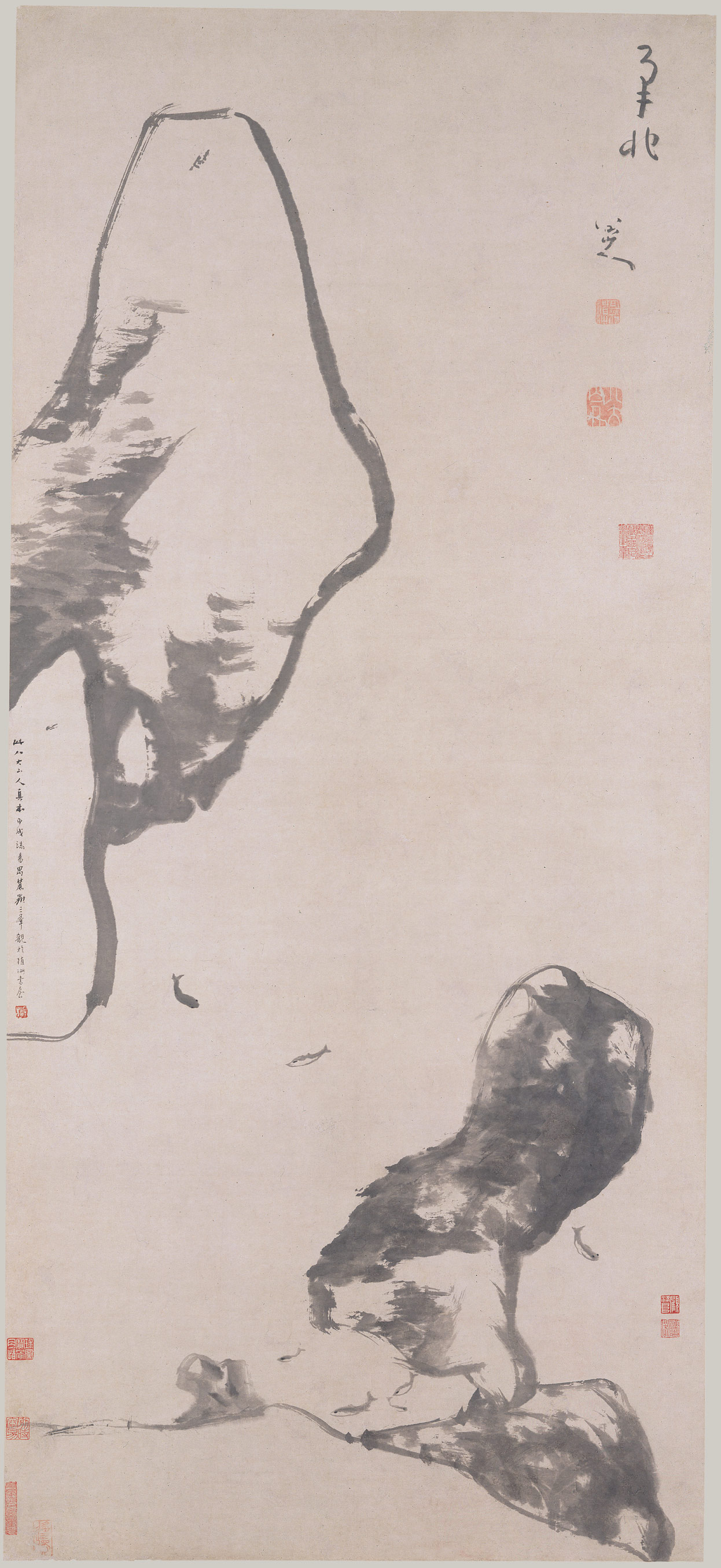

This is the third and final novella in Peirene's Small Epic series and they don't come much smaller or epic than this one. 107 pages including 11 illustrations make up 51 short chapters. Contained within those small numbers is the life of a man, the end of the Ming dynasty in China and a meditation on artistic inspiration that applies not just to the visual arts, maybe not just to the arts at all, but applies to everyone when examining what comes before action of any kind. That aspect of the book, and the fact that it is based on the real life of Chinese painter, poet and calligrapher Bada Shanren, mean that you might question how well it succeeds as a piece of fiction in the traditional sense (Weihe's Afterword and Notes on Sources show actually how well he has incorporated his research) but there is no doubt that it provides a calm and meditative read that will reward you with an enormous sense of relaxation if you can absorb it in a single sitting.

The year 1644 saw the end of the Ming dynasty which had ruled China for 276 years. The ruling family had spread far and wide but were slowly and systematically wiped out by the rising Manchu's. Those that had once wielded power were faced with the choice under the new Manchurian dynasty to collaborate or die. We follow the life of the man who was born Zhu Da in 1626, in the eleventh generation of the Yiyang branch of the Ning line of the royal family (Ning being the 17th son of Ming dynasty's founder). A sheltered childhood in the palace allowed him to develop his early prodigious gifts in poetry and art under the tutelage of his father. But with the end of the Ming dynasty and his father's death, Zhu Da is rendered mute, communicating only with his brush, before finally fleeing to the mountains, and the sanctuary of a monastery, leaving behind a wife and child, perhaps guided by wise saying, 'If you are guided by human feelings you will easily lose your way... but if you are guided by nature you will rarely go wrong.'

The year 1644 saw the end of the Ming dynasty which had ruled China for 276 years. The ruling family had spread far and wide but were slowly and systematically wiped out by the rising Manchu's. Those that had once wielded power were faced with the choice under the new Manchurian dynasty to collaborate or die. We follow the life of the man who was born Zhu Da in 1626, in the eleventh generation of the Yiyang branch of the Ning line of the royal family (Ning being the 17th son of Ming dynasty's founder). A sheltered childhood in the palace allowed him to develop his early prodigious gifts in poetry and art under the tutelage of his father. But with the end of the Ming dynasty and his father's death, Zhu Da is rendered mute, communicating only with his brush, before finally fleeing to the mountains, and the sanctuary of a monastery, leaving behind a wife and child, perhaps guided by wise saying, 'If you are guided by human feelings you will easily lose your way... but if you are guided by nature you will rarely go wrong.'The opening of this novella is a little like the paragraph above, a potted history and a lot of 'plot' and I might seem to be spoiling things by giving so much away but the plot isn't really the thing. Zhu Da leaves his life as a prince behind, any returning images 'not memories, rather the dream of a life never lived.' Within the monastery he undergoes the first of his transformations, changing his name to Chuanqui, and beginning his next period of tutelage under the instruction of the Abbott Hongmin. The meat of the book is really in what it has to say about creativity, inspiration, art, expression and the position of the person who holds the brush. The Abbott has plenty of wise advice to pass on to his charge and his training is repetitive, physical and demanding. We might not think of a single, fluid swipe of the brush as a physical exertion but we get a real sense of the pain that comes from repeatedly practising movements and getting to the point where he can remove the conscious movement and allow the hand and brush to paint what is there. As his master explains at one point: "Ink is water rendered visible, nothing more. The brush divides what is fluid from everything superfluous."

The plot will catch up Chuanqui (who in turn changes his name to Xuege, then Geshan, Renwu, Lu, Poyun and finally Bada Shanren) who will have to feign madness in order to escape being assimilated into the new order when his identity is uncovered. The adoption of the face of madness, the near-constant name changing and the desire to disappear into the act of painting all throw up interesting thoughts about the position of the artist, particularly in a modern age when the cult of the artist as celebrity or brand is so strong. Bada Shanren has an interest in remaining undetected of course and actively avoids being identified (although he applies his stamp to each of his pictures) but he is constantly striving to locate who he is as an artist for himself. Again, his master will have something to say on the path of the individual artist looking at how to express themselves directly.

'...besides the old role models you also have your own: yourself. You cannot hang on to the beards of the ancients. You must try to be your own life and not the death of another. For this reason the best painting method is the method of no method. Even if the brush, the ink, the drawing are all wrong, what constitutes your "I" still survives. You must not let the brush control you; you must control the brush yourself.'As I said at the top there are 11 illustrations of Bada Shanren's work throughout the book and one of Weihe's strengths is the way in which he technically describes the act of painting some of them. This might sound counter-intuitive but in the same way that Jean Echenoz used plain description to realise the works of Ravel into the reader's mind, Weihe describes the technique behind the paintings of Bada Shanren, something particularly important in a painting style which is all about technique and what can be achieved by single strokes, changes in pressure and the use of the right ink.

In the centre of the paper he painted a fish from the side, with a shimmering violet back and a silver belly, the tail fins almost semicircular like the bristles of a dry paintbrush. The fish's moth was half open, as if it were about to say something. It's left eye peered up to the edge of the paper with an expression combining fear, suspicion, detachment and scorn.

The eye was a small black dot stuck tot he upper arc of the oval surrounding it.

The fish swam from right to left across the paper.

Bada painted this one fish and no other, then out his name to the paper.

He had perished long ago, but he was still alive. All he feared now was the drought, when the ink no longer flowed and life had been worn down to nothing.

That is how he saw himself.

This novella is perfect reading for any visual artist (I have already passed my copy on to just such a person) but I would argue that its lessons and the thoughts it provoke would apply to anyone working in just about any field of the arts, where inspiration and creativity are as capricious and slippery as a live fish in the hand. In a modern world where everything seems to run at a hectic pace and demand is such that we might simply churn things out rather than take our time there is a lot to be said for giving this book the time it requires to read from cover to cover. That in turn might help us to appreciate the time we should take before making the first stroke, for...

....Is the whole drawing not contained in the first stroke? It must be considered long in advance, perhaps a whole life long, in order to bring it to the paper in one fluid movement at the right moment, without the need or ability to correct it.

0 comments:

Post a Comment