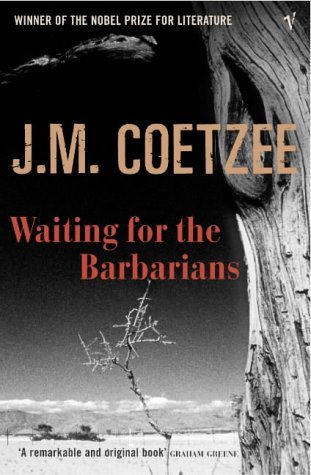

Waiting For The Barbarians - J M Coetzee

'the black flower of civilization'

I was determined not to leave it too long before tackling another Coetzee and it was only a question of which one. As I've said before, I'm a little scared of his more recent output and felt on much safer ground looking at his back-back catalogue. A few were recommended by other novelists (social networking has its genuine uses you know) and I decided to plump for this allegorical tale of oppression, control and personal morality. I always sensed that Coetzee was a writer who needed to be read, I can only reiterate my pleasure in discovering that he is a writer who demands to be read and to whom one willingly submits, each completed book increasing the chance of picking up another.

Waiting for the Barbarians was originally published in 1980 and not only picked up the James Tait Black and Geoffrey Faber Memorial Prizes, and was picked by Penguin as one of twenty Great Books of the 20th Century but was even turned into an opera by Philip Glass. The allegorical nature of the novel makes it perfect for that kind of adaptation and a worthy recipient of all its praise because it reads like an immediate classic, a novel that whilst clearly inspired by the brutal Apartheid regime in Coetzee's South Africa can also be applied universally to the ideas of Empire, control, torture and resistance. Names aren't important in this tale, our first person narrator is known only as the Magistrate, 'a responsible official in the service of the Empire, serving out my days on this lazy frontier, waiting to retire... When I pass away I hope to merit three lines of small print in the Imperial gazette. I have not asked for more than a quiet life in quiet times.' Those quiet times come to an abrupt end with the arrival of Colonel Joll and his soldiers of the Third Bureau. This far-flung outpost of the Empire is at risk from attack from the barbarian hordes that allegedly lie out there in the wilderness and are joining tribal forces in order to strike back at the Empire. A brief sortie by Joll and his men brings barbarian prisoners back to this frontier town and the Magistrate witnesses in part the brutal methods of the Third Bureau in their quest for the truth.

'First I get lies, you see - this is what happens - first lies, then pressure, then more lies, then more pressure, then the break, then more pressure, then the truth. That is how you get the truth.'

Once these interrogations are over and the men departed the Magistrate takes personal care of a barbarian girl whom he nurses back to health, the two enacting an odd, intimate and yet not sexual relationship. He wants to know what happened during the interrogation that left her partially blinded but she is reticent, leaving him with the certain knowledge that 'Nothing is worse than what we can imagine.' The Magistrate is an interesting character for all sorts of reasons but his morality is primary amongst those. A man who has clearly used his powerful position to enjoy the company of women in the past he is left stymied by the curious nature of his relationship with this barbarian girl. He even manages to find a parallel between his odd desire for her and the work of the recently departed torturers.

I cannot even say for sure that I desire her. All this erotic behaviour of mine is indirect: I prowl about her, touching her face, caressing her body, without entering her or finding the urge to do so. I have just come from the bed of a woman for whom, in the year I have known her, I have not for a moment had to interrogate my desire: to desire her has meant to enfold her and enter her, to pierce her surface and stir the quiet of her interior into an ecstatic storm; then to retreat, to subside, to wait for desire to reconstitute itself. But with this woman it is as if there is no interior, only a surface across which I hunt back and forth seeking entry. Is this how her torturers felt hunting their secret, whatever they thought it was? For the first time I feel a dry pity for them: how natural a mistake to believe that you can burn or tear or hack your way into the secret body of the other! The girl lies in my bed, but there is no good reason why it should be a bed. I behave like a lover - I undress her, I bathe her, I stroke her, I sleep beside her - but I might equally well tie her to a chair and beat her, it would be no less intimate.

He begins to question everything about his position, struggling with 'the story' of empire and the barbarian hordes that lie out there somewhere ready to attack the civilized way of life. But he also struggles to see how such an attitude might be wiped away for how do you eradicate contempt, 'especially when that contempt is founded on nothing more substantial than differences in table manners, variations in the structure of the eyelid?' From being a staunch defender of empire he begins to wish that the barbarians would indeed rise up and teach the ruling power to respect them and their history, they after all viewing the empire builders as nothing more than transients in the grand scheme of things.

If his relationship with the girl weren't enough to get him into trouble then his foolhardy journey beyond the frontier to return her to her people surely is and when he returns (without her, despite having asked her to return with him of her own free will - and after finally consummating their relationship) to the town he is summarily arrested and imprisoned. And what does he feel when he finds himself on the other side of the law? Elation, at having broken the bonds of his alliance with the Empire.

I am a free man. Who would not smile? But what a dangerous joy. It should not be so easy to attain salvation.

For what is it that he actually believes in, where does this sense of opposition come from? He is subjected to the same cruel treatment that previous prisoners have suffered but he uses his knowledge of the settlement to effect an escape from his confinement only to realise that there is nowhere for him to run away too. A prisoner of civilization itself he is able to look clearly at his oppressor whilst we the reader enjoy the same opportunity to examine our own civilization and what it is built on.

Empire has created the time of history. Empire has located its existence not in the smooth recurrent spinning time of the cycle of the seasons but in the jagged time of rise and fall, of beginning and end, of catastrophe. Empire dooms itself to live in history and plot against history. One thought alone preoccupies the submerged mind of Empire: how not to end, how not to die, how to prolong its era.

We all know the language of fear and how governments of the free world use it to justify attacks on today's 'barbarians'. As well as exploring the machinery of control through that fear, especially when combined with brutal suppression of any opposition, Coetzee dares to look at the thoughts of those who might actually wish to see those held up as the enemy triumph in order to assuage their own guilt. As the novel enters its final section, the Imperial forces seeming to have suffered terrible losses in their encounters with the barbarians, and the threat of being overrun more real than ever a strange limbo is achieved. The Magistrate, once an extension of the Empire's grip finds himself a voice of optimism, not in spite of impending doom but because of it.

Is there any better way to pass these last days than in dreaming of a saviour with a sword who will scatter the enemy hosts and forgive us the errors that have been committed by others in our name and grant us a second chance to build our earthly paradise?

2 comments:

It's the book that precipitated my reading as a serious endeavour.

Unfortunately, it was too long back (almost four years now) for me to say anything constructive about the book itself.

In his Diary of a Bad Year, Coetzee very nicely satirises his own style from here and Disgrace.

I'd recommend that you read In the Heart of the Country next.

Thanks for the comment and recommendation Ronak. It's a great book isn't it. Like you I have hundreds of books that I read before beginning this blog that I haven't been able to write posts on. Maybe I will if I ever re-read them. Anyway, I shall put In The Heart Of The Country on the list.

Post a Comment