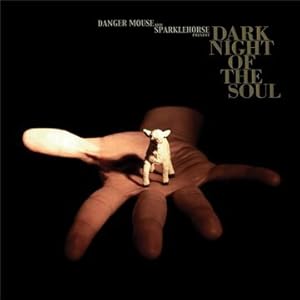

Danger Mouse and Sparklehorse present Dark Night Of The Soul

An album mired first in legal wranglings and then in tragedy finally sees the light of day and proves to be filled with at least a gem or two and a fine tribute to two of the creatives involved in it. I'm not sure I understand the exact nature of the legal problems between EMI and producer Danger Mouse that prevented the album getting a proper release initially, the photographic art book accompanied by a blank CD and instructions to 'Use it as you will' (which for most people meant downloading the music from the net). All of that silliness has been overshadowed by the suicides of Mark Linkous (Sparklehorse) and Vic Cestnutt; the former a driving force behind the project and the latter appearing on the track Grim Augury. Linkous and Danger Mouse worked together on the Sparklehorse album Dreamt for Light Years in the Belly of a Mountain but there were several works in progress where Linkous felt he couldn't do justice to the vocals. Danger Mouse suggested the use of guest vocalists and the result is this album which rises above it's dark sounding title and tragic trajectory, filled as it is with energy and creativity and where the contributing artists seem to be having fun. An album filled with collaborations can sometimes vary wildly in quality and approach and it may also depend on how you feel previously about the vocalists but there is some fine work here.

The Flaming Lips begin proceedings with Revenge, a track filled with the bitter taste and destructive nature of that notion, even whilst the beautiful strings swell and Wayne Coyne sings tenderly - 'Once we become/The thing we dread/There's no way to stop/And the more I try to hurt you/The more it backfires.' There's even a bit of auto-tune that I don't hate. Gruff Rhys (of Super Furry Animals) guests on Just War, his gentle, dreamy voice well suited to an appeal against conflict. Those, like me, who mourn the end of Grandaddy will be pleased to hear singer Jason Lytle return with a couple of tracks here, the first of which is the brilliant Jaykub, about a man who sleeps and dreams of collecting an heroic award only for a rude awakening to arrive - 'Then the alarm goes off and you're a sad man in a song.' A brilliant opening is capped off by Julian Casablancas (of The Strokes) and Little Girl which is a great little pop song that bounces along with jangly guitars as he sings of the 'tortured little girl' he's besotted with.

Less enjoyable for me are the slightly more performed (and certainly noisier) cameos of Frank Black (as Black Francis) and Iggy Pop. Weirdly, it's David Lynch himself who settles things down with his own vocal contribution on Star Eyes. There's something oddly charming and endearing about this track but it's hard to say why that is; its simplicity perhaps. Anyway, it isn't long before Jason Lytle returns with Every Time I'm With You, a slow, stumbling paean to drunken abandon. James Mercer (of The Shins) guests on the aptly titled Insane Lullaby, a track that might be a gentle number if it weren't for the chaotic noise-rhythm in the background. After having been hidden in the shadows for so long it is a joy to hear Linkous himself on Daddy's Gone, an album highlight with guest vocals from Nina Persson (of The Cardigans). It's a beautiful, sad and yet positive track -'When you lay your head/On your pillow, I'll be gone/ I'll be gone/ Will you breathe your dreams/ To your pillow like a song?' Suzanne Vega appears on the gentle tale of transformation, The Man Who Played God, a pleasant track that in no way prepares you for the nightmare vision provided by Vic Chesnutt on Grim Augury form its opening - 'We're cutting a baby out/With my grandmother's heirloom antler-handled carving knife' to the image of catfish 'wriggling in blood and gore in the kitchen sink' it is the most Lynchian of the album's tracks. The man himself returns on the closing title track, his vocals treated and reverberating as an upright piano plods along. A fittingly spooky ending to an evocative album.

You can enjoy a conjunction of sound and image below.

Dangermouse & Sparklehorse - dark night of the soul from Antonin Brault Guilleaume on Vimeo. Read more...

The Flaming Lips begin proceedings with Revenge, a track filled with the bitter taste and destructive nature of that notion, even whilst the beautiful strings swell and Wayne Coyne sings tenderly - 'Once we become/The thing we dread/There's no way to stop/And the more I try to hurt you/The more it backfires.' There's even a bit of auto-tune that I don't hate. Gruff Rhys (of Super Furry Animals) guests on Just War, his gentle, dreamy voice well suited to an appeal against conflict. Those, like me, who mourn the end of Grandaddy will be pleased to hear singer Jason Lytle return with a couple of tracks here, the first of which is the brilliant Jaykub, about a man who sleeps and dreams of collecting an heroic award only for a rude awakening to arrive - 'Then the alarm goes off and you're a sad man in a song.' A brilliant opening is capped off by Julian Casablancas (of The Strokes) and Little Girl which is a great little pop song that bounces along with jangly guitars as he sings of the 'tortured little girl' he's besotted with.

Less enjoyable for me are the slightly more performed (and certainly noisier) cameos of Frank Black (as Black Francis) and Iggy Pop. Weirdly, it's David Lynch himself who settles things down with his own vocal contribution on Star Eyes. There's something oddly charming and endearing about this track but it's hard to say why that is; its simplicity perhaps. Anyway, it isn't long before Jason Lytle returns with Every Time I'm With You, a slow, stumbling paean to drunken abandon. James Mercer (of The Shins) guests on the aptly titled Insane Lullaby, a track that might be a gentle number if it weren't for the chaotic noise-rhythm in the background. After having been hidden in the shadows for so long it is a joy to hear Linkous himself on Daddy's Gone, an album highlight with guest vocals from Nina Persson (of The Cardigans). It's a beautiful, sad and yet positive track -'When you lay your head/On your pillow, I'll be gone/ I'll be gone/ Will you breathe your dreams/ To your pillow like a song?' Suzanne Vega appears on the gentle tale of transformation, The Man Who Played God, a pleasant track that in no way prepares you for the nightmare vision provided by Vic Chesnutt on Grim Augury form its opening - 'We're cutting a baby out/With my grandmother's heirloom antler-handled carving knife' to the image of catfish 'wriggling in blood and gore in the kitchen sink' it is the most Lynchian of the album's tracks. The man himself returns on the closing title track, his vocals treated and reverberating as an upright piano plods along. A fittingly spooky ending to an evocative album.

You can enjoy a conjunction of sound and image below.

Dangermouse & Sparklehorse - dark night of the soul from Antonin Brault Guilleaume on Vimeo. Read more...