'What does it mean to live a good life?'

The Golden Mean

by Annabel Lyon

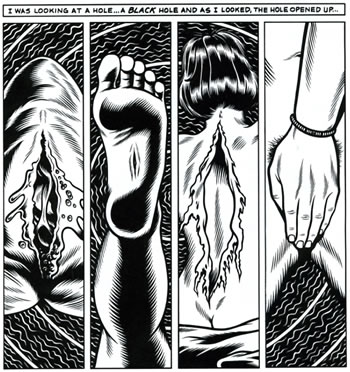

I first heard of this book when following the Shadow Giller Prize Jury over on Kevin From Canada's blog. Whilst they went on to award their top honour to The Bishop's Man (reviewed by me here) they had lots of good things to say about Annabel Lyon's debut novel which is published over here by Atlantic Books. The book's cover caused a mild controversy when ferry firm BC Ferries refused to stock it in their gift shops unless the publisher put a belly band around the offending naked buttocks, leading to inevitable headlines about a bum-rap. The picture itself couldn't be more tasteful and the idea of banning a book which makes its central characters, Aristotle and the young Alexander, so accessible is shortsighted in the extreme. Lyon has been brave to attempt to bring such ancient history to a modern readership and whatever faults there are in the book she has breathed real and surprising life into characters that feel a million miles away from present concerns.

I didn't get off to a great start with this one however. The first fifty pages or so of this book were hard going, not because there was anything particularly tough about the prose, but a large cast of characters that demands a cast list at the beginning, and more importantly the slightly dry nature of Aristotle as a character meant that I worried initially whether this was a book I'd finish. I'm glad I persevered, things definitely improve, and in many ways, perhaps fittingly, the book's strongest sections are its dialogues (or duologues). This isn't limited to those between Aristotle and Alexander by any means but before I delve into that cast list let me quickly summarise the set-up.

The book catches many of its characters at a midway point. Aristotle hasn't yet returned to Athens to set up the Lyceum, Alexander isn't yet Great, and as well as choosing a period of transition Lyon also keeps her focus away from the noteworthy historical events, the battles and intrigue, and focuses instead on the personal story behind the scenes. Aristotle arrives in Macedon with his wife, Pythias, and nephew at the invitation of Philip II who may be ruler but has a friendship with Aristotle closer to that of a contemporary. His first duty is to see whether he can effect any influence on Philip's eldest son, left physically and mentally disabled after a rumoured poisoning attempt by Philip's new wife Olympias (mother of Alexander). After that comes the tutoring of Alexander himself, always with the knowledge that a return to Athens is the 'promise' Philip has made after completing his work in Pella.

The relationship between fathers and sons is aligned with that between master and pupil. When teaching Alexander, Aristotle talks of the moment he began to challenge his own master, Plato, who responded in turn that 'it was in the nature of the colt to kick at its father.' We begin to get a sense of the fractious relationship between Alexander and his own father, and the powerful politics of succession, in a scene involving the animal that adorns that controversial cover.

Philip begins to tease him, offering him a skittish horse, daring him to ride it...The boy turns it toward the sun, blinding it, and mounts it easily. Philip, drunk, makes a sarcastic remark. From the warhorse's back , the boy looks down at his father as though he's coated in filth. That's the coin I'll carry longest in my pocket, the image I'll worry over and over with my thumb.

If Aristotle represents thought and knowledge, then Alexander of course represents action, and the golden mean of the title is the pursuit of the middle course between the two, the perfect balance for a potential ruler and indeed for any human being. Aristotle's mission remains to impress upon his pupil the value of contemplation and the danger of rashness but their exchanges only highlight the differences between the two spirits, The one insisting that whilst conquering the world makes it larger 'you always lose something in the process. You can learn without conquering.', the other responds, 'You can.' The scenes between the two of them, which could so easily have become the dry exchange of conflicting ideas, are made far more interesting by Aristotle's grasp of the psychology of a young man who is in many ways still a child but who at the same time is already beginning to show a dangerous streak of violence.

He's looking at me so brightly and expectantly, now, waiting for praise, that I falter. Such a needy little monster cub. Shall I continue to pose him riddles to make him a brighter monster, or shall I make him human?

The element of the book I really wanted to look at is the man at its centre. I have already mentioned the dryness that made it a rocky start for me and I see that a few other reviewers have identified this as the book's weakness. It is certainly true that this empirical man has a strange way of living. Sexual relations with his wife can be interrupted to make an observational note about the 'substance like the white of an egg' that appears when he works on the 'pomegranate seed' of her sex. These soften slightly after the birth of their first child and we realise that the slightly clinical approach is not simply a character trait but the behaviour of a couple struggling to conceive. What finally intrigued me about Lyon's depiction of the man is her thesis that he suffered from what we now call Bipolar disorder.

I am garbage. This knowledge is my weather, my private clouds. Sometimes low-slung, black, and heavy; sometimes high and scudding, the white unbothersome flock of a fine summer's day.

These words early on are the first hint that we receive and at regular intervals through the novel we learn more about this affliction.

There is no name for this sickness, no diagnosis, no treatment mentioned in my fathers medical books...Metaphor: I am afflicted by colours: grey, hot read, maw-black, gold. I can't always see how to go on, how best to live with an affliction I can't explain and can't cure.

His own father had diagnosed an excess of black bile, which can be either hot or cold, 'Cold: it makes you sluggish and stupid. Hot: it makes you brilliant, insatiable, frenzied.'And so Aristotle's teaching of Alexander and his own 'need to avoid extremes, perhaps because I was so subject to them.' suddenly makes the ideal of the golden mean not simply an abstract philosophical thought, or even a personal political crusade but the quandary at the very heart of the man. It may have taken a while to get there but this notion of personal balance suddenly altered my perception of Aristotle as a character and helped to anchor the book's central theme. As I said at the top, the book has its flaws, but Lyon has not only managed to wear her research lightly and thus avoid the pitfall of much historical fiction but also worked hard to unify the many extremes contained within and thereby come close to Aristotle's own desire. Read more...