Books of the Year - 2012

Last year I made a stack of my end of year picks and took a photo to head the post. This year, having moved house and with books scattered all over the place, I'd struggle to know where exactly to locate most of the books I want to bring to your attention and indeed it was a source of considerable anxiety to me that one of them, packed specially due to its unique qualities, went missing for nigh on a month before it was finally relocated and hurriedly placed on a special shelf for safekeeping.

Anyway, 2012 has been a year filled with enjoyable books, some of which have been very special indeed. Keeping up the blog has been a struggle at times but messages of support have turned up often just when I need them and the enthusiasm of others has always been helpful when a shot in the arm has been required. I'll be absolutely honest and say that next year really will see my posts becoming more sporadic but as long as you really want to hear what I have to say then I will try and make the effort when a book really demands it. Twitter remains an exciting place to learn and share about books and when I pretty much lost the ability to update the blog recently it was there that I managed to keep talking and enthusing about what I was reading.

Below you'll find my picks of the year, a varied collection as always, books that I found in a variety of ways. I've summarised why they made the cut below but please click on the titles to read my in-depth reviews and hopefully you'll find something that you hadn't wanted to buy... until now.

Absolution by Patrick Flanery

I read this debut near the beginning of the year but it has stayed in my mind as one of the year's best new novels, heralding the arrival of a nicely matured voice in fiction. Perhaps the most conventionally 'literary' novel on my list it actually has a rather complex structure with four narrative strands and changing viewpoints. Flanery tackles South Africa's fraught politics but also the weight of personal history and the very nature of truth itself. Ambitious and well executed it's a great read now and a very positive indication hopefully of what's yet to come.

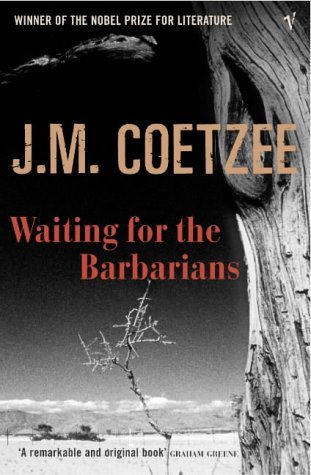

I read this debut near the beginning of the year but it has stayed in my mind as one of the year's best new novels, heralding the arrival of a nicely matured voice in fiction. Perhaps the most conventionally 'literary' novel on my list it actually has a rather complex structure with four narrative strands and changing viewpoints. Flanery tackles South Africa's fraught politics but also the weight of personal history and the very nature of truth itself. Ambitious and well executed it's a great read now and a very positive indication hopefully of what's yet to come. It's not all about new books and this novel from Coetzee helped to cement him in my mind as a true master. This allegorical novel of violence, oppression and control is written with the kind of universality that makes it feel like a classic; names of people or places are not important, neither is a sense of when or where exactly the novel is set. The unflinching manner of Coetzee's approach makes for an exhilarating and uncomfortable read. A novel that challenges the reader with its views and opinions but leaves you to draw your own conclusions; what more could you ask for?

It's not all about new books and this novel from Coetzee helped to cement him in my mind as a true master. This allegorical novel of violence, oppression and control is written with the kind of universality that makes it feel like a classic; names of people or places are not important, neither is a sense of when or where exactly the novel is set. The unflinching manner of Coetzee's approach makes for an exhilarating and uncomfortable read. A novel that challenges the reader with its views and opinions but leaves you to draw your own conclusions; what more could you ask for?A Death In The Family by Karl Ove Knausgaard

Not many books made such an impact on me as this controversial novel and that's why when I was asked to pick just a single book from this year's output by Kim over at Reading Matters, this is the one I plumped for. Knausgaard made a Faustian pact when he decided to write about himself and his own family and the notoriety that has accompanied the publication of his six-volume, fictionalised autobiography is as impressive as the sales figures in his native Norway. Part one looks at drunken adolescence, the death of his father and the alcoholism of his grandmother. The final third is about as a grim a piece of writing as I have ever come across. A book that had me scratching my head about half way through had me itching for more when I finished the final page and with part 2 due next year I can only hope that there are plans to translate and publish the following four books.

Not many books made such an impact on me as this controversial novel and that's why when I was asked to pick just a single book from this year's output by Kim over at Reading Matters, this is the one I plumped for. Knausgaard made a Faustian pact when he decided to write about himself and his own family and the notoriety that has accompanied the publication of his six-volume, fictionalised autobiography is as impressive as the sales figures in his native Norway. Part one looks at drunken adolescence, the death of his father and the alcoholism of his grandmother. The final third is about as a grim a piece of writing as I have ever come across. A book that had me scratching my head about half way through had me itching for more when I finished the final page and with part 2 due next year I can only hope that there are plans to translate and publish the following four books. Humour. Let's be honest, it's all too often missing from the books of many 'serious' readers apart from the odd flash here and there so when a book comes along that makes you actually laugh and smile with recognition throughout then what a joy that is. Bachelder's take on modern fatherhood is hilarious, beautiful, touching and true. Little vignettes, often of just a page in length cover the final three months of Abbot's wife's second pregnancy. Just the titles of some chapters are enough to elicit a laugh and the real skill is in not allowing the book to suffer any slumps along the way. A perfect gift for any men you may know who are perhaps expecting another arrival anytime soon.

Humour. Let's be honest, it's all too often missing from the books of many 'serious' readers apart from the odd flash here and there so when a book comes along that makes you actually laugh and smile with recognition throughout then what a joy that is. Bachelder's take on modern fatherhood is hilarious, beautiful, touching and true. Little vignettes, often of just a page in length cover the final three months of Abbot's wife's second pregnancy. Just the titles of some chapters are enough to elicit a laugh and the real skill is in not allowing the book to suffer any slumps along the way. A perfect gift for any men you may know who are perhaps expecting another arrival anytime soon.All Quiet on the Western Front

by Erich Maria Remarque

A genuine classic that will have you mouthing the familiar refrain of those who finally tackle one of those books they always knew they should have read: 'why didn't I read it sooner?' There's not much for me to say here about Remarque's classic war novel other than that it gave me something completely fresh to think about after I'd been performing in War Horse for a couple of years, that it was a distinct pleasure to give copies of it away on World Book Night and that it's exactly the kind of book that was never in any danger when I had a book cull before moving house recently.

A genuine classic that will have you mouthing the familiar refrain of those who finally tackle one of those books they always knew they should have read: 'why didn't I read it sooner?' There's not much for me to say here about Remarque's classic war novel other than that it gave me something completely fresh to think about after I'd been performing in War Horse for a couple of years, that it was a distinct pleasure to give copies of it away on World Book Night and that it's exactly the kind of book that was never in any danger when I had a book cull before moving house recently.Leaving The Atocha Station by Ben Lerner

Not dissimilar to the book above, this is another novel with little plot, a diary-like narration and lots of digression but poet Lerner's debut novel has a wicked sense of humour and a fairly repellent hero whom you can't help but be charmed by. An American poet abroad on a fellowship in Madrid smokes spliff, takes pills, experiences culture and generally bullshits his way around his research project. Along the way he questions his validity as poet, man and lover and we enjoy one of the most stimulating debuts since ... well, the book above.

Championed by bloggers all over the place but none more so than John Self in the pages of The Guardian this is a novel that more than justified the fervour behind it. I had been looking forward to it after my first experience of his writing but I wasn't expecting it to be quite as a good as it was. Ridgway's own irreverence as a writer is either extreme humility or an indication that he, along with most of the reading public, doesn't realise exactly how good he is. The novel is bold and formalistically daring, written with an ease and brilliance that must make other writers want to give up and has a variety and scope that means each reader is sure to identify a different section or sentence as their favourite bit of writing this year. Believe the hype.

Swimming Home by Deborah Levy

My favourite read from this year's Booker list was a triumph for small publisher And Other Stories and I very nearly included another of their titles, Lightning Rods by Helen De Witt, in this list but decided to mention it here and free up one of these limited berths for another fabulous book (very briefly, Lightning Rods is a whip smart satire that is funny, clever and shocking - read this review for more). Levy's novel is slim but packed full of resonant images, enigmatic characters and telling details. There's a wonderful darkness that clouds proceedings and seldom has there been such an enjoyable sense of being unsettled.

My favourite read from this year's Booker list was a triumph for small publisher And Other Stories and I very nearly included another of their titles, Lightning Rods by Helen De Witt, in this list but decided to mention it here and free up one of these limited berths for another fabulous book (very briefly, Lightning Rods is a whip smart satire that is funny, clever and shocking - read this review for more). Levy's novel is slim but packed full of resonant images, enigmatic characters and telling details. There's a wonderful darkness that clouds proceedings and seldom has there been such an enjoyable sense of being unsettled.Look, I don't know how many times I have to tell you to read Denis Johnson but will you please just READ DENIS JOHNSON. The fact that the Pulitzer board didn't award a fiction prize this year is bad enough but the fact that they did it when a novel(la) like this landed in their laps in downright scandalous. Johnson's collection of writings is so eclectic and varied that it's difficult to say exactly where this fits in the cannon but as a fan of his I can say that I was surprised by the richness and reward that came from such a slim book, previously published as a story in the Paris Review, thankfully given the proper treatment by Granta who had a storming year with three titles in this best of list.

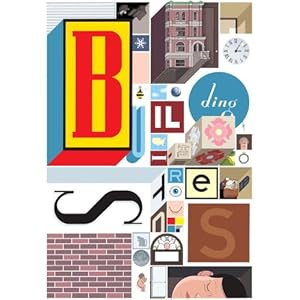

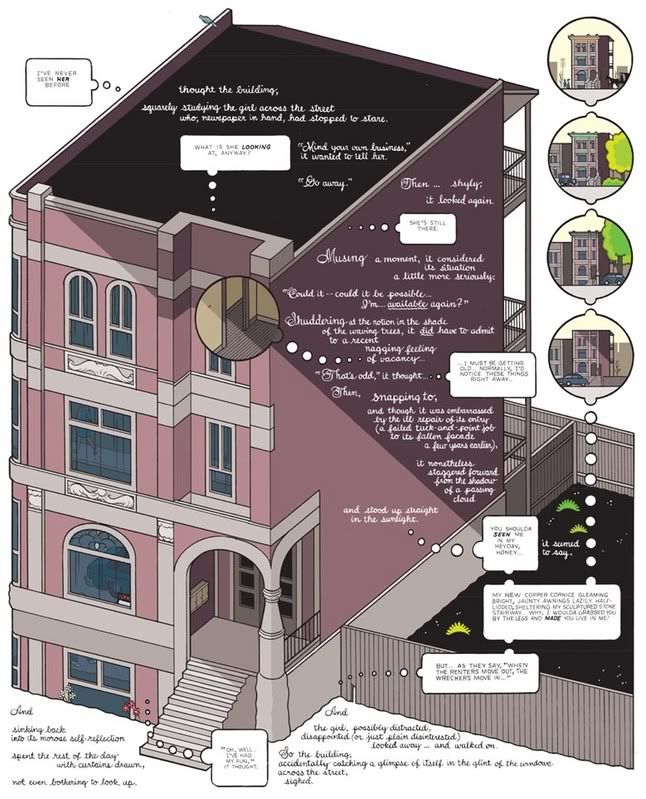

Building Stories by Chris Ware

What to say about this extraordinary creation? This is the book I mentioned at the very top that went missing in transit and caused me moments of genuine anxiety as I worried that I might not be able to lay my hands on a replacement copy without bankrupting myself even further. Chris Ware opened my eyes to what the graphic novel could be when I read his first book Jimmy Corrigan. I am eternally grateful to him for that because since then I have derived so much pleasure from reading more and more graphic work. For him then to return with a ... I hesitate to call it a book because it is so much more than that ... with such a gift is quite astounding. A book which cements the place of the graphic novel amongst 'serious' literature and shows at the same time how limited its supposed superiors really are, this will no doubt be seen in years to come as a definitive work.

Also worthy of note: Mrs Bridge, Dr Haggard's Disease, Seven Years, Days of the Bagnold Summer and so many more.

Emperor's New Clothes: HHhH and The Yellow Birds.

Read more...