2011 - Books of the Year

Yes, you may have already noticed that 2011's end of year post is just about books rather than also including my favourite music, films and other cultural highlights. The reason for this is quite simple: I've barely listened/watched/been to any as any regular readers will have noticed over the year. It has in fact been all I could manage to maintain a steady stream of book reviews this year and I have my fingers crossed about being able to do the same next year. It hasn't been easy. But every time I think I'm about to throw in the towel something comes along to make me persevere and I'm always glad that I do. The books below are all brilliant for different reasons and a couple of them are so good that they're worth writing the blog for alone. And then of course there's you and your comments.....

Many thanks to every single one of you who has read my blog this year and a seasonal hug and kiss to everyone who's left a comment. I can't tell you how much I appreciate it.

A Taste of Chlorine by Bastien Vives

It may be at the bottom of the pile in the photo above but this graphic novel is right at the top of my books of the year. If you want to read a graphic novel that truly uses pictures to tell a story that words wouldn't have been able to then this book is perfect. The story of a boy using swimming to help treat curvature of the spine is all about body-language, gesture and movement. There's hardly any text and yet volumes are spoken in Vives' exquisitely drawn panels, with the underwater environment particularly well presented, you can almost smell the chlorine. Like reading a perfect short story it is enigmatic, moving and left me with a warm glow in my heart.

A genuine masterpiece about tyranny and control from a writer who may only have produced two novels in his long lifetime but who made sure they were both in their own ways completely brilliant. This novel examines the symbiotic relationship between a man who is clearly Jewish (though never named as such) in 1930's Germany (though this is never made explicit) and the leader, or adversary, (clearly Hitler though again he is not named) who tyrannises him. Brave in its hypotheses, brutal in its psychological insights and honesty, this novel is a classic because it manages to be about all situations in which one group makes a pariah of another. Indispensable.

Great House by Nicole Krauss

This novel is by no means perfect but its failings come from ambition rather than lack of talent which Krauss seems to have in spades. There is a feeling that comes from reading the work of a mature writer, an ease that you are in the hands of someone who has something to say. This usually comes from writers far more experienced than Krauss but her maturity is just one of the attractive features in this novel about a desk and the various hands it passes through, characters created with such detail that they cease to feel like characters at all, and the novel as a whole written with a complexity that forces the reader to slow down and appreciate the thought, intelligence and humanity that has gone into creating it.

A collection of stories so unique, so specific, so perfect as to need little more than that from me to send you straight out to buy a copy. Pancake died without ever really knowing just how good a writer he was and too young for us to know just how good and influential he might have become. As it stands several writers cite him as an influence and the warmth and reverence with which they do this is worth noting. His stories embody the area of West Virginia in which Pancake grew up, with authentic details and voices but these aren't simply stories rooted in a particular geography so that we can indulge in a kind of literary tourism, he also shows with a couple of stories just how formally inventive he might have been. Just buy the damn book, ok?

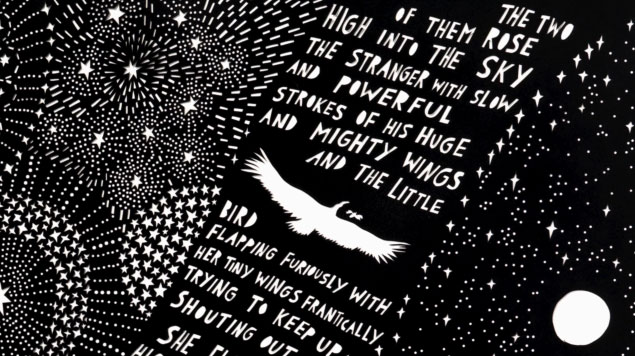

The Summer Of Drowning by John Burnside

I have no shame in admitting that I am a fan of Burnside and take a small amount of pride in being one of the voices that has helped convince John Self over at Asylum to read more of him and realise just how good he is (although in his own end of the year round-up he mentions that he did so in order to shut people like me up). This latest novel shows a writer at the height of his powers returning to a story he failed to complete a decade ago and delivering a novel filled with atmosphere, unease, myth, storytelling, artistry and writing so good it sometimes make you want to take a moment and nod your head in appreciation. Set in the Arctic Circle and drawing on the folk myths of the area this is a book infused with the spectral light of the midnight sun; deeply unsettling, wonderfully complex, another weapon in my arsenal to make sure that you all make the effort to pick up one of his books. Soon.

An unalloyed pleasure from first page to last, Towles debut is a perfectly mixed dry Martini. Set in 1920's New York it tells the story of a life-changing year for Katherine Kontent, the only fictional character I have ever fallen in love with. Taking inspiration from Walker Evans' candid subway photographs Towles effortlessly recreates an era and peoples it with characters in which I believed totally and couldn't hope to forget. It's the kind of novel where you genuinely care about what happens to them and can't help but wonder what happens to them after the final page. Witty, funny, smart and beautiful: that's just Katey Kontent, but also a good description of the novel as a whole.

Lazarus Is Dead by Richard Beard

One of the most exciting reads of the year for the way in which its form was hard to pin down, Beard's 'novel' is a re-examination of the story behind one of Jesus' miracles. By taking an almost forensic approach Beard manages to tell the story more fully than ever before, bravely hypothesising about the childhoods of both men, drawing inspiration and evidence from other artistic sources, research into the period and of course the invention of the author. Structured around the number seven the chapters count down to Lazarus' death and then back up again after his resurrection, where Beard is brave enough not just to imagine what happens to the story of Lazarus after its usefulness in the Bible ends but to posit an even greater significance for the man who came back from the dead. If you want to know why fiction can still be exciting then pick this book up.

If I had a pound for every novel that takes a male protagonist, wipes his memory and then starts from there then I'd have a load more money to spend on books, but this novel from linguist Marani is ingenious and far smarter than most. A man is found badly beaten on the quay in Trieste in 1943. When he comes to he has no memory of who he is or even which language he speaks. The Finnish doctor on a German hospital ship that treats him presumes that he is also Finnish after spotting a name inside his coat and an initialled handkerchief and so begins to re-teach him his language in the hope it will unlock memories and lead him to recover his identity. This relatively slim novel covers huge themes around memory, identity and truth and manages to intrigue even further with the perspective from which it is written. Exactly the kind of novel I would hope to unearth on this blog (although Nicholas Lezard gets the credit on this one).

I Am A Chechen by German Sadulaev

A book that melds memoir with fiction, folk tale with fantasy, Sadulaev's account of the conflict in Chechnya doesn't fit into any easy categories and is all the more exciting for it. It may not be consistent but the early sections in particular are stunning in the way they weave Chechen myth with personal testimony to create something that manages to be grand and specific at the same time. Infused with the guilt of a man who wasn't there when things were at their worst, Sadulaev uses his creativity instead to speak on behalf of a people and give voice to a conflict the like of which all too easily passes us by on the ticker tape of rolling news.

This is hardly news to anyone as the book was already well regarded by the time I came to read it at the very beginning of this year but it has remained very strong in my mind, a perfect example of why we should all read more literature in translation. Bakker's novel is written with the kind of quiet confidence that let's the reader relax in the knowledge that they are in safe hands. Reserved to the point of repression, the prose mimics the flat landscape of rural Holland but gives little hints along the way of the power that lurks beneath the surface. A farmer and his father inhabit a lonely farmhouse and the son's appalling treatment of his father leads us to wonder what might have happened in the past. Bakker expertly releases fragments from the past in his examination of love, loss and the special bond between twin brothers.

The Horseman's Word by Roger Garfitt

I don't tend to read an awful lot of non-fiction but I'm lucky that when I do it tends to be first rate. This memoir was literally forced into my hand by an excited publicist and her enthusiasm wasn't misplaced. The prose is beautiful as you might expect from a poet and its evocations of childhood innocence are heart-warming and comforting. When it follows Garfitt's misadventures at university and beyond it becomes a fascinating portrait of a mind unravelling and the writing shows the tissue-thin barriers between lunatic, lover and poet. A book that took many years to write and hone, and the passion of one publisher in particular to finally bring to print, this is a labour of love and madness that rewards the effort.

Over a decade after it was originally published and won the Booker Prize I finally get over my Coetzee hoodoo and discover just why this book, and writer, are so well regarded. A Cape Town university professor is forced to leave in disgrace after an affair with a student and goes to stay with his daughter on her smallholding. When the two of them are subjected to a brutal assault by three black men South Africa's fragile new politics are laid bare for examination. A brave and uncomfortable read that retains its ability to shock, this is a novel filled with anger and love, containing so many ideas and themes that you could happily discuss it for hours and hours. It has also of course made me want to read more Coetzee. Ah well, there's always next year....

And a few books that came close and deserve honourable mentions: At Last by Edward St Aubyn, A Visit From The Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan, From The Mouth Of The Whale by Sjón and Today by David Miller. Read more...