'the reverse of a shadow'

Austerlitz

by W.G. Sebald

Well it took almost two years to make good on my promise to read some more Sebald after The Emigrants but I got there in the end. It took a fair bit of planetary alignment: a lovely hardback found in a charity shop for a bargain price of £3, a passing comment in a conversation I had with an author about one of my favourite books of the year, and the publication of an essay by James Wood in the LRB. All those nudges finally pushed me headlong into Sebald's final book before his premature death at just 57. In the spirit of the trepidation that accompanied my move to read it I have also been terrified of writing up my thoughts on it, this is after all a vast book by a supremely intelligent writer, chock-full of weighty themes and ideas and the considerable weight of the Holocaust bearing down on it too. I shall therefore focus on a couple of aspects that I found interesting and leave you safe in the knowledge that there is far more to discuss than I could hope to cover right here for the moment (if you'd like to read a lengthier post from another book blogger then may I recommend Tom's over at A Common Reader).

As ever we have a narrator that it might be too simple to presume is Sebald himself, this is 'fiction' after all, and a chance meeting that provides the book's narrative. In the late 1960's, during a period of regular trips to Belgium, Sebald meets on several occasions the same man, Jaques Austerlitz. The pair meet first in the waiting room of the central station in Antwerp where they discuss their shared interest in architecture. The anatomy of buildings, their cultural and political significance, the ways in which they express something about the humans who created and built them will all be discussed and as someone whose general interest in architecture extends to watching the odd episode of Grand Designs it's worth noting that some of these extended thoughts are fascinating. The grandness of some of these buildings is forbidding and yet at the same time, as Austerlitz notes, revealing.

Yet, he said, it is often our mightiest projects that most obviously betray the degree of our insecurity. The construction of fortifications, for instance....clearly showed how we feel obliged to keep surrounding ourselves with defences.

As the two men enjoy each other's company, bumping into each other repeatedly, we sense that we are being prepared for the real narrative and so it is twenty years later that the two men meet again, in a rail terminus once more, this time London's Liverpool Street Station, and Austerlitz reveals that he has been looking for someone 'to whom he could relate his own story, a story which he had learned only in the last few years and for which he needed the kind of listener I had once been in Antwerp.' This is because Jaques Austerlitz had actually been raised as Dafydd Elias, evacuated from Europe on the Kindertransport and raised by a pastor and his wife in Bala, Wales. It is just before his school exams that he receives the shocking news that the name he must legally write on the papers is not the one by which he has gone for so long, but a name which feels immediately alien.

At first, what disconcerted me most was that I could connect no ideas at all with the word Austerlitz. If my new name had been Morgan or Jones, I could have related it to reality. I even new the name Jaques froma French nursery rhyme. But I had never heard of an Austerlitz before, and from the first I was convinced that no one else bore that name, no one in Wales, or in the Isles, or anywhere else in the world.

His discovery soon afterwards that Fred Astaire was actually born to a Viennese father with the same surname comes as scant consolation. What Austerlitz is left with, what any of us would be left with where we to be told that everything we thought we knew about ourselves was built on shaky foundations, is a gigantic void which he needs to fill. I couldn't help but be reminded of one of my favourite books of the year, New Finnish Grammar, which tells the story of a man rendered a blank slate after a terrible beating, presumed to be Finnish, who learns from scratch the language he hopes will unlock who he really is. It is this aspect of Austerlitz that I found fascinating and it is a sense that there had always been something not quite right that he latches onto immediately.

It is a fact that through all the years I spent in the manse in Bala I never shook off the feeling that something very obvious, very manifest in itself was hidden from me. Sometimes it was as if I was in a dream and trying to perceive reality: then again I felt as if an invisible twin brother were walking beside me, the reverse of a shadow, so to speak.

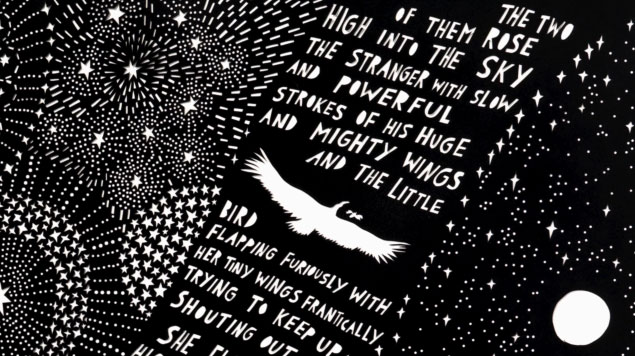

In his search for memory, for that is what he must undertake in order to learn and understand from where he came, Sebald's trademark photographs play an important role. These photographs are presented throughout the text to illustrate people and places that 'Sebald' or Austerlitz make reference to. We cannot help regard at least some of them as genuine as the text that accompanies them describes the photo exactly as we see it and yet we know that apart from a few which look as though they have been taken by Sebald for the book, most of these images are found and have been appropriated for this fiction. That striking photo on the front cover for example of the young Austerlitz dressed for a ball, 'the unusual hairline running at a slant over the forehead...the piercing, inquiring gaze of the page boy who had come to demand his dues, who was waiting in the grey light of dawn on the empty field for me to accept the challenge and avert the misfortune lying ahead of him.' So convincing and yet of course Austerlitz is a fiction, this is some other boy, the only clue on the back of the photo in Sebald's archive are the words "Stockport: 30p" The book is filled with moments like this where we have to remind ourselves that what we are both reading and seeing is not real, but it is also worth reminding ourselves that whilst the construction isn't 'real' every episode of fear, exile and death within the book was someone's reality.

When Austerlitz travels to the Czech Republic, quite literally going through the phonebook Austerlitz's, and meets Vera, a woman who had served his family, a slew of photographs, testimony and memory comes back and with the pictures in particular we get a real sense of 'the mysterious quality peculiar to such photographs when they surface from oblivion.'

...as if the pictures had a memory of their own and remembered us, remembered the roles that we, the survivors, and those no longer among us had played in our former lives.

Photography is also used as a metaphor for memory itself.

In my photographic work I was especially entranced, said Austerlitz, by the moment when the shadows of reality, so to speak, emerge out of nothing on the exposed paper, as memories do in the middle of the night, darkening again if you try to cling to them, just like a photographic print left in the developing bath too long.

This emergence of memory is clearly a classic Sebald theme and the murk that surrounds it is repeated several times in the recurring image of the darkening light of dusk. When the two men first meet in Antwerp 'Sebald' has already compared the dusk of the station to the light in the Nocturama at the local zoo. The shadowy space of that waiting room has an otherworldy quality perfect for memories to emerge from and much later in the book, when the scene shifts to Liverpool Street Station, the concourse is cast as some kind of entrance to the underworld.

Even on sunny days only a faint greyness illuminated at all by the globes of the station lights, came through the glass roof over the main hall, and in this eternal dusk, which was full of a muffled babble of voices, a quiet scraping and trampling of feet, innumerable people passed in great tides...

The book is haunted by these passing ghosts; the weight of the Holocaust I mentioned earlier is a very real and oppressive thing, and in fact as Austerlitz's story is revealed I found myself becoming less and less interested in the actual details but rather more fascinated by the descriptions of the mechanics of their recovery. The waiting room in that metropolitan underworld for example becomes the place where memories come flooding back.

In fact I felt, said Austerlitz, that the waiting room where I stood as if dazzled contained all the hours of my past life, all the suppressed and extinguished fears and wishes I had ever entertained, as if the black and white diamond pattern of the stone slabs beneath my feet were the board on which the end game would be played, and it covered the entire plane of time.

Austerlitz is a book I could go on discussing for much longer as I said but I hope that what I have already raised is enough to recommend it. It isn't perfect by any means; some have suggested it is in fact his 'least best' book, and as well as having to surmount the challenge of the often relentlessly paragraph-less pages I definitely thought the book was strongest in the first third and collapsed under its own weight at times later on. But there is no doubt that Sebald is a writer who has to be read by any serious reader, I just hope it won't be another two years before I pick up another of his volumes. Read more...